Updated 10.17.19

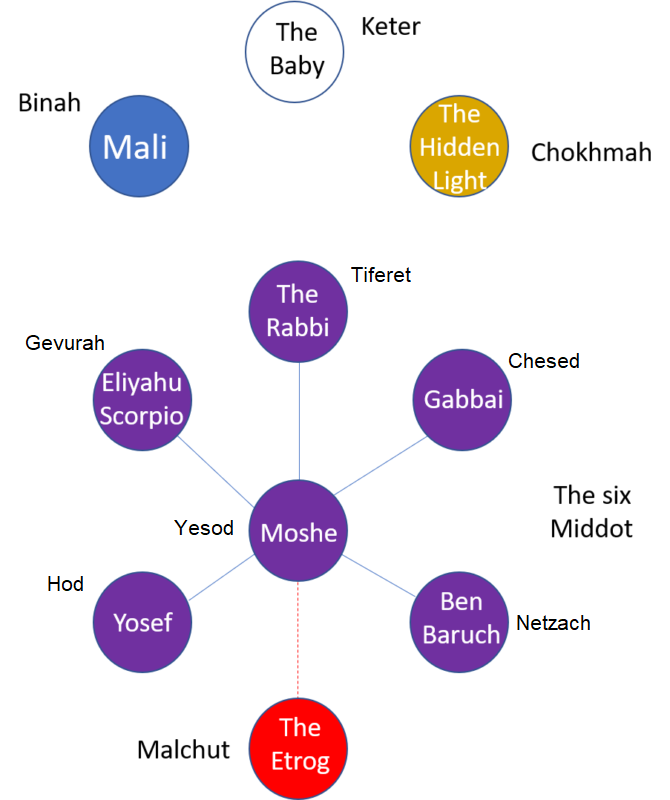

The main characters in the movie have an association with the Sefirot, which are the ’emanations’ or ‘characteristicis’ of G-d that permeate creation, especially in human beings, who are “made in the Image of G-d.” This is very important regarding main character — Moshe Bellanga.

The lower seven are also called ‘middot’ (singular: ‘middah’) which are “emotive attributes” and ones we are directly involved with in our lives. See https://www.inner.org/sefirot for more advanced concepts on the Sefirot

The dynamics between these characters, their attractions and friction, cause a number of changes to occur within Moshe as well as the other characters. Some of these changes are stressful and may even appear as ‘bad’ in some way, but they are all part of G-d’s plan of rectification for each of them. This is the concept of Tikkun Middot (repair of attributes) which is a key part of the framework of the movie.

It is important to note that every character, (and each of us) has the entire spectrum of the ten Sefirot. As in real life, one or more of these may tend to be more dominant in our personality and behaviors.

Moshe’s main role is that of the ‘tzaddik’ (righteous person) whom the story centers around. The Sefirah of Yesod (Foundation, Connectivity) is associated with the tzaddik, who is the one with the potential to connect the physical world, associated with Malchut (Kingdom, Receptacle) to all the spiritual worlds above.

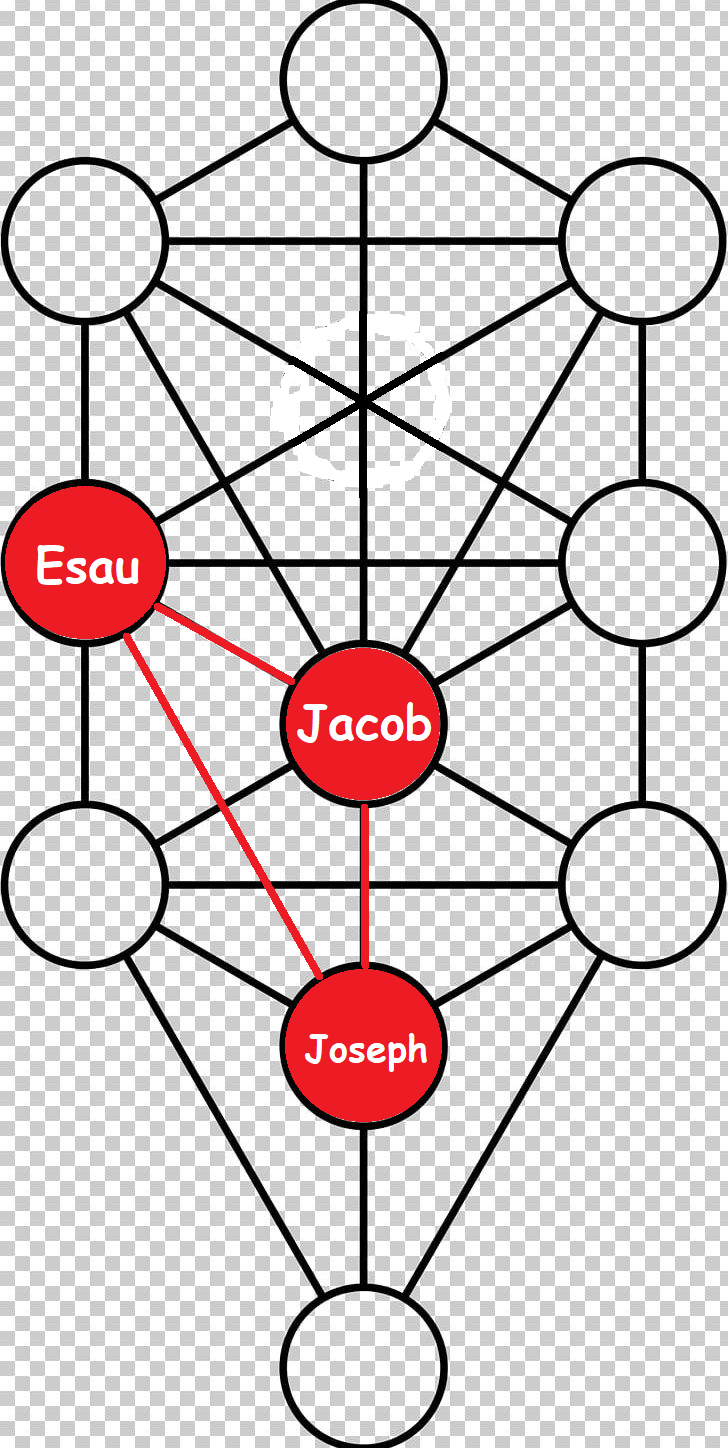

Above Yesod in the diagram, is Tiferet (Beauty, Harmony, Truth). This is the role of Moshe’s rabbi, who represents the aspect of emeth/truth. Tiferet and Yesod, along the “central path,” have a very close relationship. Tradition places Jacob at Tiferet and his son Joseph at Yesod.

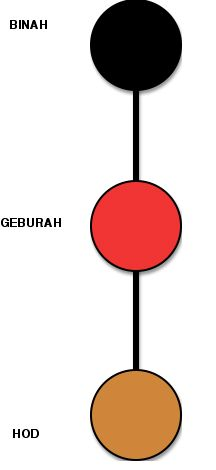

On the left (constrictive) side of the diagram are the two antagonists, Eliyahu and Yosef, who fulfill their respective roles of Gevurah (Judgment) and Hod (Reverberation). It’s important to remember that the Sefirot are neither good or bad. Any of them, in our own lives, can manifest in ways that assist or deter our own rectification.

It is also a Torah principle that significant spiritual change is preceded by tzimtzum, a constriction that ‘makes room’ for new insight. Such constriction can manifest in any number of ways, often in the form or trials and tribulations. As we will see in the movie, Eliyahu and Yosef create the necessary changes for Moshe and others.

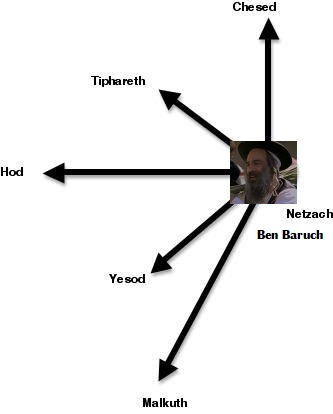

On the right, ‘expansive’ side of the middot, are Gabai, who is at Chesed (Lovingkindness) and Ben Baruch at Netzach (Initiative). Though they play the role of “good guys” (compared to Eliyahu and Yosef), they too are in need of tikkun. Gabai still becomes judgmental and angry (the opposite of Chesed), and Ben Baruch has “boundary issues” that he needs to learn (which is a function of Hod).

All four of the characters on the left and right sides have their own issues to resolve, to come into proper balance. This is also the case with these Sefirot (Chesed, Gevurah, Netzach, Hod) within Moshe Bellanga himself.

Beyond the seven lower Sefirot/Middot, are the three upper ones. (These are called the ‘mochin’ meaning intellect.) Mali plays the role of Binah/Understanding (called the “upper mother”). The ‘conditions’ facing her husband (and the other characters) are often set by her, such as; wishing to have a child, sending Moshe out to pray, rebuking Moshe and herself for how they treated their guests, leaving Moshe to go to her mother’s home, and sending Moshe to see the rabbi. This idea of G-d constantly “setting the conditions” in our lives, is a function of Binah which is the power to distinguish and differentiate.

The Sefirah of Chokmah (Wisdom) is associated with “existence, but outside of creation.” In the Torah, (in English) this is seen in the first four words of Genesis, “In the beginning Elohim …” Up to that point in the text, we are looking “before or outside of Creation.” Beginning with the word for ‘created’ (bara) we enter the world of creation. This is the level of the Ohr Haganuz – the Hidden Light, also at times referred to as Orh Ein Sof, depending on context.

Finally, “present yet hidden away” in Keter (until the end of the story) is baby Nachman. Correlating to this, is the Etrog at Malchut, which contains “the blessing to have a boy” – or in this case baby Nachman. As is taught from the text of Sefer Yetzirah, the beginning is in the end, and the end in the beginning.

SPOILER ALERT (Sort of) …

One can view the story of Ushpizin as what was required for a “rectified Moshe” at Yesod, which would lead to the connection being made between the Etrog at Malchut and Mali at Binah (the blessing for a boy and her having the child). The six Sefirot between these two are the path in need of repair.

Another principle surrounding the etrog is Moshe’s great desire for it. Though one should always “hurry to do a mitzvah,” there are three things to keep in mind.

- Is your intention pure?

- Is the timing correct?

- Is there something else Hashem wants from you (or someone else) that needs to occur?

These are questions that may be asked regarding the Moshe and the etrog, as well as in other scenes in the movie.

These are some of the important moments in the movie that relate to spiritual concepts. We discuss these in depth in our online conferences. We break up the movie into six parts as follows:

PART 1

3:42 – Moshe and Ben Baruch meet

Ben Baruch (representing Netzach) is the ‘energizer bunny’ who initiates action – sometimes without thinking it through (lacking the balance provided by Hod). The movie starts with his “spark” (lit under Moshe!) to make things happen for Sukkot.

The attribute of Netzach, on the right side of the kabbalistic “Tree of Life,” diagram is often the pro-active first step that “gets the ball rolling” in the physical world. With regard to the traditional seven Ushpizin associated with Sukkot, Netzach is associated with Moses.

5:00 – The “Pushka Man”

Here is an early example of Hashgaha Pratit and the level of subtlety in the movie. This man was born prone to headaches in the sun. Because of this ‘disability,’ he ends up working indoors and collecting donations inside a cafe. It is here that he ‘happens’ to run into Eliyahu and Yosef, and helps them to find Moshe. Without this ‘arranged meeting’ (by G-d), there is no connection. His long-time illness enabled him to perform a critical mitzvah, one with “ripple effects” – yet he likely remained unaware of this.

5:10 – The “Yetzer Hara Man”

A second minor character who introduces a major concept. His words on constantly being alert to the Yetzer Hara (“evil inclination”) underlie the entire movie. The yetzer hara can be a difficult concept to tackle. On the one hand, it seems the source of us “getting into trouble.” On the other hand, everything from G-d is for an ultimately good purpose. Is it either or both? Something else?

Also, some people struggle greatly in dealing with their yetzer hara, while for others, they “manage to manage” it fairly well. So it is a difficult thing to overcome or not? This topic is addressed throughout Torah literature.

These two citations shed light on this:

“In the future, G-d will bring the yetzer hara and slaughter it before the righteous and before the wicked. To the righteous, it will have the appearance of a towering hill; and to the wicked, it will have the appearance of a strand of hair. Both the former and the latter will weep; the righteous will weep, saying, ‘How were we able to overcome such a towering hill?’ The wicked also will weep, saying, ‘How is it that we were unable to conquer this strand of hair?’ And the Holy One, blessed be He, will also marvel together with them”

Sukkah 52a

“So too the Holy One, Blessed be He, said to Israel: My children, I created an evil inclination, which is the wound, and I created Torah as its antidote. If you are engaged in Torah study you will not be given over into the hand of the evil inclination, as it is stated: “If you do well, shall it not be lifted up?” (Genesis 4:7). One who engages in Torah study lifts himself above the evil inclination.”

Kiddushim 30b

Some key points relating to the movie:

- As mentioned by the character, the Yetzer Hara often rises up just when “heaven is about to bestow a blessing.”

- The Yetzer Hara can be energized by things we consider ‘good’ (like $1,000 showing up under your door!)

- Note the reference to ‘eating’ in Sukkah 52b above. This can only take place at the end of the age, once certain rectifications have taken place. There is a correlation to Moshe Bellanga’s ‘eating’ of the etrog, which he would never do on his own, but “G-d arranges” when the time was right. (See notes to 1:17:40 below.)

8;20 – Dialogue between Mali and Moshe

Count the references to the word “understand” in this conversation. (This comes up again near the end of the movie.) This is the Sefirah of Binah (= Understanding) which relates to the future. (Chockmah/Wisdom relates to the past). Binah is also the sefirah through which G-d “sets the conditions” in our life for us (day by day, moment by moment), which is rectified via the “path of teshuvah” (return to our true self) which is one of tikkun middot. (See Themes.)

11:30 – Moshe and Mali’s methods of praying.

This is a wonderful representation of two main ways of praying. Mali prays from the ‘left,’ utilizing the structure of the Siddur. Moshe is from the ‘right’ and ‘freestyles’ it, talking directly to G-d as in a conversation. With either ‘method,’ the goal is to elevate our awareness toward “G-d’s perspective.” See “Prayer’s Function,” at www.13petals.org/prayers-function.

13:40 – The counting to ’35’

A little mystery they seem to have thrown into the script. The two men arrive at this number at the same time that Moshe is praying to be a “good Jew.” The name Yehudah (from where ‘Jew’ comes) has a gematria of 35.

PART 2

15:45 -Gabbai’s Sukkah

Ben Baruch (at Netzach) is the ‘tactical’ aspect of Chesed above (which is Gabbai). Beb Baruch, knowing Gabbai has a newer Sukkah, takes the old one for Moshe, without asking. Gabbai becomes upset over this action, later accusing Ben Baruch of “ruining his holiday.” This is an inappropriate response and is indicative that even Gabbai/Chesed needs rectification in the story. Ben Baruch, as well, mush learn to “look before he leaps,” which is the aspect of proper Hod within Netzach. In a sense, Gabbai’s reaction lacked consideration as much as Ben Baruch’s did.

17:20 – The cafe dialogue with Eliyah, Yosef and Pushka Man

This is a key moment in the movie, showing the hidden hand of G-d in the lives of those serving Him (Hashgaha Pratit). Aside from this ‘chance’ meeting (which goes back to “pushka-man’s” divinely orchestrated health issue), the tiny bit of tzedakah that Eliyahu gives “to the Ohr Haganuz yeshivah” helps make a connection.

There are also several hidden references to “Jerusalem below” and “Jerusalem above” in the conversation between Eliyahu (Gevurah) and Yosef (Hod), which is another type of connection to be made, as G-d “does not enter Jerusalem above until He can enter Jerusalem below” (Talmud, Ta’anith 5a). This relates to the connection between Mali (Binah = upper Jerusalem) and the Etrog (Malchut = lower Jerusalem).

19:00 – Song lyrics (Atah Kadosh)

This song (in the background) is from the perspective of there being “many paths” in life to negotiate. The final song of the movie speaks of the total unity of G-d. The first (our experiences in the Olam Hazeh) leads to the latter in the Olam Haba.

ATAH KADOSH

There are many paths we travel, To seek a drop of truth.

I didn’t hesitate to nibble, At the delicacies of sin.

We couldn’t discover, a single taste to ignore.

This culture wasn’t for us, It was a fire in our hearts.

And I am the child, The least of everything,

I stand here trembling and amazed.

And I am the child, The last in the nation,

I stand here flustered and thrilled.

Because you are holy, And your name is holy

Holy every day, You will be praised, selah!

The temporary material is wasted, The instinct of the snake is to lie,

When I close my eyes, Finally the truth becomes clear.

It is difficult to comprehend common sense, And imagination is disappointing as well,

But there is a Leader to do the job, And He loves us.

And I am the child…

22:00 – Mali’s comments about what the money will be for

Mali says she has it “all figured out.” This is the attribure of Binah, however there is a defect in her ‘understanding’ as she is delving in the details, without seeing the bigger, unified, picture (See103:55).

23:20 – Gabbai’s comments regarding his missing sukkah

Gabbai’s comments show how he (as Chesed) needs his own rectification. He begins by speaking negatively of a fellow Jew and as we will see, this develops into great anger. Later in the movie, he is ‘compelled’ by both Moshe and Ben Baruch to forgive them.

PART 3

29:30 – Eliyahu and Moshe dialogue

Chesed descends from Chokhmah (the hidden light – see above Cafe scene) and is extended to even those not entirely meriting. Moshe (the tzaddik) is “judged” (Gevurah/Eliyahu) by Eliyahu, who indirectly asks Moshe if Chesed is to be extended to the left side (to he and Yosef) as well. This is a tactic of haSatan, the adversary, who cleverly misapplies Torah to trip us up.

31:45 – Mali and Moshe dialogue

Moshe, from the right side (at Chesed) sees all the positive benefits of these two ushpizin. Mali, at Binah, is pondering the details. Both his enthusiasm and Mali’s concern’s need a measure of rectification. The balance will be found “between them” at Tiferet (the rabbi) later in the movie.

36:35 – Yosef’s comments

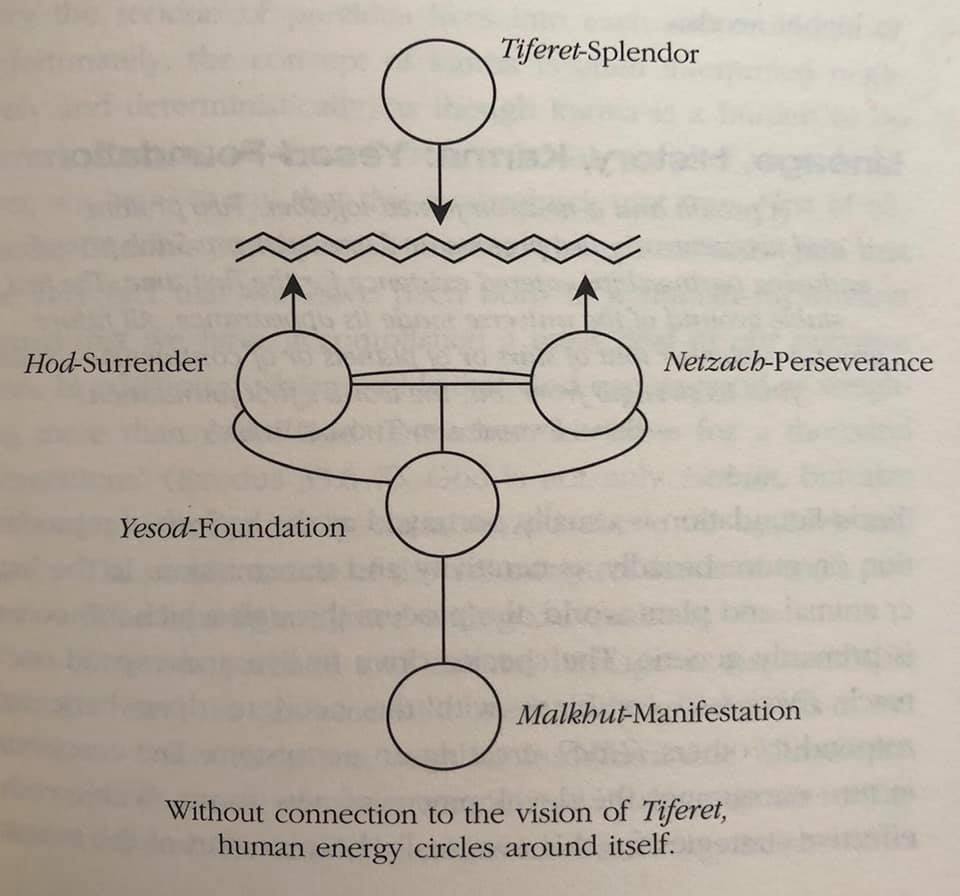

The words spoken here are an example of how the character of Yosef receives input and processes it – a function of the Sefirah Hod. His process needs repair however, as it is separated from the ‘truth’ at Tiferet. (See diagram to the left from, “The Gift of Kabbalah,” Tamar Frankiel, p. 79.)

38:40 – Eliyahu and Yosef dialogue

Eliyahu’s perspective is pure Gevurah/Judgment. Yosef (at Hod/Reverberation) processes all the possibilities. These are two main functions of the ‘left’ side.

40:30 – Mali’s question

“So how come they showed up like that?” The question relates to the Tzimtzum (constriction) being introduced here, as the far-away answer is, “for the benefit of Moshe and Mali themselves.” Many such constrictions will occur for them to “see more clearly” regarding how G-d was operating.

42:00 – Moshe’s discussion of Ohr Haganuz

“Nichnas yayin, yatza sod” —“When wine goes in, secrets come out.” Moshe’s rant may contain truth, but the timing (they’re all drunk) is not the best. Then again, G-d works in mysterious ways.

43:30 – Eliyahu provoking Moshe

There are many rectifications in the movie, the primary one being anger – something that Moshe has never totally dealt with. So what does G-d send him to help with this defect? Someone to make him angry, of course. In fact, the only person in his life that could push him to the necessary limit, where he has no one to turn to but G-d.

PART 4

45:15 – Moshe and the Rabbi – first dialogue

The two discussions with the rabbi are critical as he represents Tiferet, the aspects of truth and balance, based on the all-important understanding that G-d is the only power (Ein od milvado) and that all that happens is for the good (Gam zu l’tova).

This first conversation centers around Eliyahu and Yosef (Gevurah and Hod from the left side of restriction). Moshe mentions two things; His wife Mali is “sort of happy,” and his two guests are “not holy.”

This is where we see the unity of Tifefert that the rabbi brings. Mali’s happiness is directly related to Moshe understanding why these “unholy guests” are now in his life. The rabbi says that it’s a good thing such unholy guests are there as Moshe can bring tikkun to them. (And thus himself.)

He also states that making Mali ‘happy’ is Moshe’s “way of worshiping” (e.g., avodah, his work/task for G-d). Her happiness is ultimately having a child, something that will occur once all the necessary tikkun takes place (in Moshe and the rest of the six male characters)

47:00 – Ben Baruch and Gabbai dialogue

Ben Baruch (Netzach) finds his rectification as shown in his comment on helping one Jew and harming another, finally balancing his “natural initiative” with the contemplation of Hod. (See https://www.aish.com/sp/k/Kabbala_20_Netzach_and_Hod_Means_to_an_End.html for more on how Netzach and Hod function.)

Gabbai (=Chesed) has his tikkun come from forgiving Ben Baruch unconditionally. The connection between these elements of the right side is re-established when Ben Baruch insists on a hug. As Gabbai says, to him “Who can resist you?” (i.e., Netzach’s constant initiative.)

48:10 – Moshe overhearing Yosef and Eliyahu’s conversation

A key moment. Moshe forgets the advice from his rabbi and also the “yetzer hara man.” (See 5:10 above.) Instead of “dealing with things,” he sends the two of them away.

49:15 – Moshe’s prayer and subsequent false statements to Eliyahu and Yosef

Moshe cannot “see past the choices he does not understand.” (A Matrix movie concept related to Binah.) His choices come from “within” his physical circumstances and not the deeper reality of G-d being in control.

51:15 – Mali and Moshe dialogue

Mali (Binah) shares insight into the opportunity they missed with the challenge (tzimtzum) their guests presented. Here she is an instrument of G-d, setting a (new) condition as mentioned earlier.

52:20 – Yosef’s insight

Again, Yosef as Hod processes information that he relates back to the pure Gevurah of Eliyahu. Their return is all part of Hashgaha Pratit.

52:50 – Mali and Moshe dialogue

Mali recognizes the sneakiness of the yetzer hara in Moshe’s error, but will experience a similar situation herself later. As mentioned, the yetzer hara can be clever and devious.

54:00 – Return of Eliyahu and Yosef

Another ’round’ with the attributes of the left side, which is now far more ‘energized’ due to Moshe and Mali’s own errors (lying, etc.) The situation will require greater wisdom and understanding on the part of Moshe and Mali. Again, this is G-d’s own ‘hidden’ plan.

58:30 – Eliyahu’s statement

“What’s right is right.” A statement of pure Gevurah, leaning toward ‘truth,’ which is the Sefirah of Tiferet. (Tiferet is the related aspect of, “putting first things first,” as found in “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People,” by the late Stephen Covey.)

58:40 – Mali’s prayer

As with Moshe, G-d will give you what you need to do true teshuvah, even if it’s not what you expect and hurts. Even tribulation is part of Hashgaha Pratit.

PART 5

59:15 – Mali’s conversation with Yosef and Eliyahu

The only scene with all three characters from the left (Binah-Gevurah-Hod) together and interacting. Mali (Binah) is ‘mother’ to Gevurah (Eliyahu) and by extension to Hod (Yosef). Subleties abound from Mali counting and dispensing money, Yosef analyzing the books, and Eliyahu touching the mezuzah on his way out.

1:01:40 – Moshe’s discussion with Ben Baruch

Moshe is seeking understanding, but his attempt to do this by looking at a sequence of events in the physical realm, again causes him to reach inaccurate conclusions. He firmly believes he has arrived at the answer to why things have happened the say they did, but his judgment does not see past his present level of understanding.

1:02:25 – The party, and reactions from the community

Tikkun extends into the community, again in a way that is in no way evident. There is even a charge of ‘blasphemy’ between factions. This comes from the ‘division’ caused by some of them speaking evil against Eliyahu and Yosef, who are “not so holy,” but remain Jews. The Hebrew term for blasphemy is ‘gadaph,’ which comes from a root meaning to ‘cut’ (in terms of causing separation). Causing separation within Israel is considered blasphemy, as G-d, Torah and Israel are ‘one.’

1:03:55 – Moshe’s conversation with himself based on his understanding

“Now I understand everything,” he says, Again, the yetzer hara sees an ‘opening,’ causing Moshe to draw conclusions based on his limited understanding of reality at that moment in time.’ (Compare to Mali at 22:00)

1:04:40 – Moshe’s chat with Gabai

This reflects a concept in Jewish law of asking for forgiveness three times. This benefits both Gabai as well, as he had strayed into improper judgment.

1:06:20 – The mess created outside and within the sukkah

The scene of physical disruption coming from the left side (Eliyahu and Yosef) is reflective of “unbalancing the equation” – A Matrix movie concept explained by the figure of the Oracle, who represent Binah, the head of the left side in that movie trilogy.

1;09:20 – Mali’s rage based on her level of understanding

Separation and reunification is often required to create a more perfected connection. It is described as a three-step process of hachnaah (submission), havdalah (separation), and hamtaka (sweetening). These relate to the right side of expansion, the left side of restriction and the balance of the middle. (Similar to the concept of; thesis, antithesis and synthesis.)

1:11:05 – Moshe’s explanation based on his understanding

Moshe again cannot see past the choices he does not understand.” He will soon cry out for greater ‘understanding’ (Binah), a key theme to the movie going back to his first argument with Mali at 8:20 (above). Again, “breaking through” one’s present level of understanding requires some sort of tzimtzum/restriction of whatever is “in the way” of acquiring that.

PART 6

1:13:20 – Moshe and Eliyahu’s perspectives

Here, Eliyahu reflects the attribute of Gevurah being overcome by ‘truth’ – “What’s right is right,” as he earlier said. The faithfulness of the tzaddik, Moshe, and compassion (rachamin) of the rabbi, have initiated the final phase of the rectification process.

This “triad” of Eliyahu at Gevurah being “overcome,” by Moshe at Yesod and the Rabbi at Tiferet, may be seen as reflecting a verse from one of the prophets.

“And the house of Jacob shall be fire and the house of Joseph a flame, and the house of Esau shall become stubble, and they shall ignite them and consume them, and the house of Esau shall have no survivors, for the Lord has spoken.”

Obadia 1:18

FOLLOW THE ETROG

The etrog takes on major symbolism in three consecutive scenes.

1:14:30 – The phone call

Moshe holds the etrog (the “lower female/Malchut) in his hand as he speaks to Mali (the “upper female/Binah) on the phone. Entering between the two are the words Mali speaks … “go to the rabbi.” The rabbi represents the truth of Tiferet that will play a major role in the unification.

Note that for “some reason” Moshe fails to put the etrog back in its box, leaving it on the shelf exposed – where Yosef later finds it. (Hashgaha Pratit!)

1:15:20 – Moshe’s second conversation with the rabbi

The rabbi’s insight focuses on Moshe’s main area requiring repair – his anger – which can block the path to Binah (Mali) and is overcome by prayer.* Note the rabbi holds up the etrog as he speaks of this.

The rectification of all the characters and the associated attributes centers around the deep truth the rabbi brings – that everything is “of G-d” – except their choices. There is deeper discussion on this at the end of this page.

(* According to Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, prayer is “the main weapon of Mashiach.”)

1:17:40 – Eliyahu cutting the etrog and the meal served to Moshe

This is perhaps the most profoundly deep moment in the movie. Moshe could never cut and eat of the etrog as this would violate Torah. This action had to come about in a ‘divinely sneaky’ way, where neither Eliyahu or Moshe was aware of what was happening.

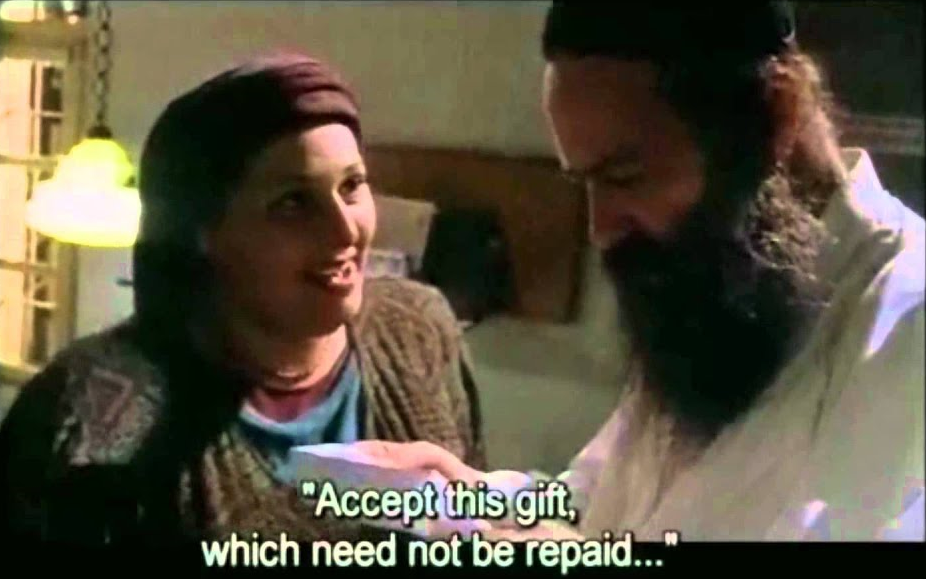

The etrog as Malchut, is the ultimate receptacle. receiving all of which is done through the Sefirot above it. As such, the teshuvah of Eliyahu and Yosef (as well as Gabai and Ben Baruch) is “in the etrog.” By ‘consuming’ of the etrog, these rectifcations “enter Moshe” and via the six rectified middot within him, he will become the ‘connection’ between the etrog and Mali, causing the blessing within the former to come into reality with them having a child – providing he does one last thing related to his anger issue.

Hashem often works in such ‘mysterious’ ways, even on a grander scale. Author Tamar Frankiel offers another example with a similar theme:

“This brings us to another crucial principle that appears in the writings of the Ari and especially in the kabbalah school of the Gaon. Along with the law of parallelism, there is yet another cosmological law that King Solomon formulated. This law states: There is a time when the (evil) man subjugates the (good) man to his own undoing (Ecclesiastes 8:9). In other words, the forces of good must temporarily suffer at the hands of evil, in order to undermine those very forces by extracting and drawing out aspects of the fallen forces of good that are being held there in captivity. The principle of “a time for subjugation” is the second reason why the higher knowledge of Mashiach ben Yoseph is forced to go into exile. His soul must be subjugated to captivity, abuse and, under specific circumstances, even temporary loss of identity, in order to redeem specific ‘inverted’ fragments of Supernal Wisdom. Only by the captor believing that the captive is under his control can the captive get close enough to ‘draw’ out the imprisoned energies from the soul of the captor himself. The “bad guy” thinks he is winning and yet he is ultimately losing to the “good guy.” The catch is, however, that in order for this mode to operate successfully, not only can’t the “bad guy” know the truth, the “good guy” as well cannot really know what is going on. In fact, the “good guy” can’t always even know that he has been turned “inside-out” and that he is in a present state of captivity – also known as assimilation. This is an insurance policy. It guarantees that the divinity of Mashiach ben Yoseph will always be protected whenever it is forced to go into exile among the klippot.”

The Gift of Kabbalah, Tamar Frankiel, P. 87

(See more below regarding Moshe and Eliyahu both being “in the dark” about G-d’s plan but “playing their roles.”)

1:19:45 – Moshe’s outrage

Moshe’s anger reaches a point that he has to deal with it. His anger, for the first time, is a “holy anger,” and he throws himself upon G-d’s mercy, in a ‘prayer with tears’ which “breaks through all barriers” as it taught.

“I have heard your prayer; I have seen your tears”

2Kings 20:5

1:21:10 – Moshe’s crying out for “understanding”

Another deeply mystical moment. Having now rectified all six of the middot within himself and also having consumed of the etrog, the final connection to be made is with Binah/Understanding. Moshe does this by pleading to G-d for Understanding/Binah. This is the final unification. He has completed this path of ‘teshuvah‘ (=Binah), which is also known as “tashuv-hey”, meaning the restoring of the lesser letter Hey at Malchut, to the greater letter Hey at Binah.

Down a “rabbit hole” we go

“Three things only come when people are not thinking about them – Mashiach, a found object, and a scorpion.” – Sanhedrin 97a

The above reflects a Torah concept reflected in the movie, one related to the idea of “thesis, antithesis, synthesis.” Moshe’s desire for a child and the etrog with the blessing in it (the “found object”) is the thesis. The question here becomes, “Is Moshe seeking a child based on his own desire, or does it come out of his love for G-d?”

It would be a difficult thing for him to truly know the answer to this, as he has lived a very insular life for years. The ultimate test is placed before him – a test of his true desire. When everything falls apart, will he turn back to his old ways or stay true to Hashem?

Along comes the antithesis, Eliyahu Scorpio (the ‘scorpion’) to test him, and in the process help Moshe rectify something that he had not completely dealth with. Moshe had been living a “religious life” since his “early days” of being a “tough guy.” Only Eliyahu (someone from that past) can get him angry like he has not been in years.

Anger is a very unholy act, causing us to revert back, forgetting the commandments and that G-d is the one behind the ‘conditions’ in our lives. Moshe gets angry, however he turns it into “righteous anger,” when he falls apart and turns to G-d in the most emotive way a human can, bringing the final rectification he needed.

Eliyahu, as the antithesis (Moshe’s personal ‘satan’), created the friction that prompted the change needed to come to the ‘synthesis’ – baby Nachman, who arrives as a type of ‘Mashiach’ in the life of Moshe (see below). Thus, the etrog, Eliyahu and the baby function in the roles of the three unexpected things from Sanhedrin 97a and present the connectivity between them.

The hidden things belong to the L-rd, our G-d

Moshe purchased the finest etrog he could find, but even using it ‘properly’ was not enough for the “blessing to have a boy” to be realized, due to his own unrectified attributes. Once he “passes the test,” Eliyahu sees that Moshe truly is what he ‘appeared’ to be (a tzaddik) and then ‘judges’ him (the ‘neutral’ attribute of Gevurah) accordingly.

What we now see is a radical change in Eliyahu (= Gevurah). His repentance represents the redemption of the “evil realm.” Though gevurah is ‘neutral’ (as are all the sefirot) ‘evil’ comes from the restriction of the light of G-d, and ‘restriction’ is a function of Gevurah.

Acknowledging the change in Moshe, and that he and Yosef “went too far’,” Eliyahu is now acting in the ‘opposite’ role of chesed, an aberration of his “normal self” (e.g., cleaning the sukkah, making a meal for Moshe). The key here is that no one else could cut the etrog but Eliyahu, performing something that would usually be considered ‘evil,’ but here done out of pure chesed.

The rectified aspects of Eliyahu get “put into the salad” via the etrog, which, representing Malchut (the receptacle), is where all of these things are brought together (e.g., Moshe, Eliyahu, Yosef, Mali, the baby). Eliyahu elevated the etrog to the level that Moshe could integrate it, and all these things in it, into himself. He could now eat the etrog (unknowingly), taking in the essence for the blessing for a son. The required condition (from G-d) had been met by Moshe.

Bringing this all back to Sukkot

This transformative concept goes into the deepest areas of Torah.

Returning to the beginning of Sukkah 52a:

“In the future, G-d will bring the yetzer hara and slaughter it before the righteous and before the wicked.

This relates to a deeper concept related to Sukkot. One of the re-integrating of ‘evil’ into the system. This is also known as the “consuming of the leviathan” in kabbalistic literature. What is quite amazing here is what is done with the skin of this slain leviathan – a permanent sukkah will be made out of it for the righteous.

“In the future, the Holy One, Blessed be He, will make a feast for the righteous from the flesh of the leviathan, as it is stated: “The ḥabbarim will make a feast [yikhru] of him” (Job 40:30). And kera means nothing other than a feast, as it is stated: “And he prepared [va’yikhreh] for them a great feast [kera]; and they ate and drank” (II Kings 6:23). And ḥabbarim means nothing other than Torah scholars, as it is stated: “You that dwell in the gardens, the companions [ḥaverim] hearken for your voice: Cause me to hear it” (Song of Songs 8:13). This verse is interpreted as referring to Torah scholars, who listen to God’s voice. (See 1:24:00 below.) And with regard to the remainder of the leviathan, they will divide it and use it for commerce in the markets of Jerusalem, as it is stated: “They will part him among the kena’anim” (Job 40:30). And kena’anim means nothing other than merchants, as it is stated: “As for the merchant [kena’an], the balances of deceit are in his hand. He loves to oppress” (Hosea 12:8). And if you wish, say that the proof is from here: “Whose merchants are princes, whose traffickers [kinaneha] are the honorable of the earth” (Isaiah 23:8). And Rabba says that Rabbi Yoḥanan says: In the future, the Holy One, Blessed be He, will prepare a sukka for the righteous from the skin of the leviathan, as it is stated: “Can you fill his skin with barbed irons [besukkot]” (Job 40:31). If one is deserving of being called righteous, an entire sukka is prepared for him from the skin of the leviathan; if one is not deserving of this honor, a covering is prepared for his head, as it is stated: “Or his head with fish-spears” (Job 40:31).”

Baba Bathra 75a

The previously mentioned concept of, “thesis, antithesis and synthesis,” can be seen as relating to the Baal Shem Tov’s idea that all spiritual service entails three developmental stages of consciousness: submission, separation and sweetening. It is not by chance that before the scene of the meal prepared by Eliyah, Moshe visits his rabbi, who says he is a “sweet” man – one who has done well in rectifying his characteristics (middot).

Note that at the end of that scene, the rabbi (who represents the truth of Tiferet) strongly reminds Moshe about not getting angry, which happens to be the final challenge Moshe is about to face. The scene ends with the rabbi kissing the etrog and gazing upward. In a “split second,” the film shifts over to Eliyahu ‘smelling’ his etrog just before cutting it, and then squeezing some juice onto the food Moshe will eat. In kabbalah, the concept of a kiss and concept of ‘smell.’ The ‘circuit’ from the heavenlies to the belly of Moshe is completed.

1:24:00 – Final scene and song lyrics

Ultimately, it is Moshe, functioning in the synergizing and connecting aspects of the sefirah of Yesod, that makes the connection between below and above, ushering in the ‘hidden mashiach’ – baby Nachman. All the characters come together around baby Nachman. This is the unified world of Atzilut where souls connect and from where the Ohr Haganuz, the “Hidden Light” — was “set aside for the use of the righteous in the World to Come” (Mesechta Chagigah 12b). “Ohr Haganuz” is also name of the Yeshivah, as the Ohr Haganuz is stored in the words of the Torah, and partly accessible through study. (See the connection of Torah study to the consuming of the Leviathan in Baba Bathra 75a above.)

YESH RAK HAKADOSH BARUCH HU

One must pass in this world through some confusion,

Some obstacles, some changes, until he understands

A man has to pass this world on a very narrow bridge

And the truth is sharp, like a strand of hair,

And the main thing is not to be afraid at all

We’ve got to rejoice and never forget what we really are

There is G-d. There is only G-d

The last line of the song and movie is, “There is G-d. There is only G-d.” This is the great concept of “Ein Od Milvado” – “There is no power but Him.” It is the lesson taught at Purim: The same G-d who sent Mordechai also sent Haman. It applies to everyone and everything entering the lives of Moshe and Mali in the story as well.